I still have a hard time calling the Internet, “The Internet.” Frequently, I will call it, “The Wire.”

I still catch myself saying, “I saw a story about that on the wire.”

The “Wire” refers to a literal wire. The wire was a phone line.

For many of my 25 years in broadcasting, the wire was how stories reached the radio station and, in turn, the masses.

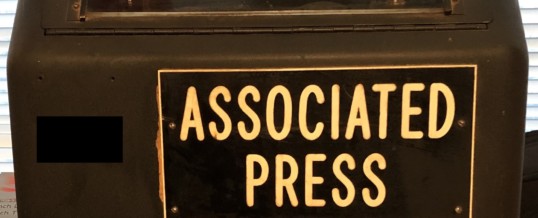

For a subscription fee, the Associated Press (AP), United Press International, and other news services transmitted breaking news, weather, sports, and other information to radio, newspapers, and television stations across the country. The AP is still in business.

Most news outlets had at least one wire service, and in my experience the most widely used was the AP.

The data was transmitted from the wire service down a phone line to the media outlet and into an AP machine.

The machines were a lot like a big typewriter. They had inked ribbons and used a box of paper that fed through the bottom. The paper folded inside a big box and was several feet long.

The machines were fairly large, clunky, prone to eating the paper, and weighed as much as a Buick.

They were also slow. At least compared to today’s standards.

The machine printed at 60 words per minute. To get some idea of how slow that is compared to what you’re used to today, imagine using your current iPhone or home computer on AOL dial-up.

In the late 1980s, dot matrix printers became far more practical, faster, and cheaper to maintain. So, the old AP machines became obsolete.

I remember the station manager asking the AP repairman what he was supposed to do with the old AP machine when it was replaced.

The AP guy said, “That’s your problem.”

The AP didn’t seem to want them back, so most of the machines that I knew of wound up in the dumpster.

I remember thinking what a shame that was. I’d been in the business about five years at the time, and even during my short tenure I’d personally ripped stories from the wire that are now in the history books.

I was on the air the night John Lennon was murdered. December 8, 1980.

The AP alarm went off (it was a light that came on in the control room – the AP machine was in a separate room in the building) and I got up and walked to the wire to see:

***Bulletin-Bulletin-Bulletin*** John Lennon is dead.

That’s all that it said. More information wouldn’t come until a bit later.

Being a huge Beatles fan, I became numb. All hopes of a band reunion were gone, and the voice of a generation was now silent. I assumed his death might be drug-related, but I never thought that someone would shoot him.

I broke the news on-air and the switchboard lit up. I spent the rest of the night taking requests and playing his music.

In 1986, a normal midday show became wall-to-wall reporting after the AP alarm went off.

***Bulletin-Bulletin-Bulletin*** The Space Shuttle Challenger has exploded.

Other news stories that are now part of history also came across the wire. Too many to count or recall.

Fast forward.

I’m scrolling through Facebook one day and was very surprised to see one of the old AP machines for sale. I was even more surprised that it had survived.

I contacted the lady in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to find out more.

She shared that her father had passed away and he also had been a radio announcer. He and I had been close in age. The difference between the two of us was that related to the radio business, he had kept anything and everything he could. I had not.

He not only kept the AP machine when the station threw it out, he had kept news stories from the machine (wire copy as we called it) that dated back to the 1960s. The stories he kept included JFK’s assassination, and the breakup of The Beatles.

She said that most of the wire copy went with the machine.

We agreed on a price and my wife and I joined she and her husband for lunch in Texarkana. Afterward, we loaded the AP machine into the back of our Prius.

The car sank a bit.

I closed the trunk lid and off we went toward home.

“What are you going to do with that thing?” my wife asked.

“Display it in my recording studio,” I answered.

But the real question was, display it to whom? I’m about the only one who ever goes in there.

Time passed and I showed it to a few friends who stopped by. They were polite about it, but I could tell that the relevance of the machine was only apparent to me.

The AP machine needed to live somewhere else. Somewhere that it could be seen and understood for the value it had.

I knew that I shouldn’t keep it. I decided I would keep most of the wire stories, but the machine needed to be in front of the public.

A few years ago, I donated my antique radio collection to The Texas Broadcast Museum, located in Kilgore, Texas. My friend Chuck Conrad, who is still in radio, built that museum from scratch. He was the first person I thought of.

So, I called him.

“Chuck, do you have an AP machine in the museum?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “But I could always use another one.”

Chuck and I quickly made a deal over the phone.

I delivered it to him on a Friday. While I was there, I saw my old radio collection on display and many other remnants of broadcast history, including an old ESPN live truck, a restored 1940s Dallas television station mobile broadcasting bus, recreations of radio station control rooms, and much more.

We shook hands and as I was leaving Chuck told me how much he enjoyed my newspaper column.

I thanked him. Not only for saying nice things about the column, but also for being the guy who took on the task of making sure that all of the tools of the trade used by broadcasters over the last 75 years were assembled in one place for all to see.

And I encourage you to go see it.

The museum is open to the public and tickets are very affordable. You can get more information at texasbroadcastmuseum.com.

While you’re there, look for my old AP machine. It’s now where it belongs.

©2019 John Moore

John’s book, Write of Passage: A Southerner’s View of Then and Now, is available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble. You can contact John through his website at www.TheCountryWriter.com.

APR

2019