Growing up, movies weren’t just a Saturday night diversion. They were lessons, warnings, and often, thanks to amazing writers of the era, meant to make us think.

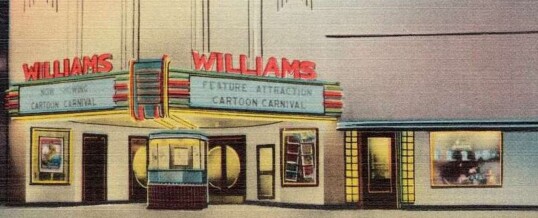

Hollywood was turning out stories that carried more weight than Flash Gordon and other serials of the 1930s. And for a boy like me, sitting in Williams Theater in Ashdown, Arkansas, those films shaped the way I thought about just about everything.

What I didn’t realize until years later was that these movies weren’t just reshaping me; they were also reshaping culture. And in some cases, they were saving the very companies that made the movies.

The 1967 movie Bonnie and Clyde wasn’t just a gangster picture, it was a cultural earthquake. Even as a kid, I could see how it fascinated the adults. And this was a movie about murderous thieves. But Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway played the outlaw lovers with a mix of charm and menace that unsettled older audiences but electrified the young. When I saw it, people were rooting for them.

Gene Hackman showed just how dangerous and human supporting characters could be. This movie dared to make outlaws look glamorous while also showing the bloody consequences of what they did.

For a Southern boy who had heard about the Depression-era desperados in real life, it was a confusing mix of bad and more bad. The movie also changed Hollywood’s direction.

Warner Brothers had been struggling, but Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the “New Hollywood” era, when directors and writers were suddenly freer to break taboos and speak directly to younger audiences. The studio found not just a hit but also a new identity, powered by riskier stories.

One of the films that truly changed how I saw growing up and the relationship between those who had already lived life, and those who were just beginning theirs was the 1972 film The Cowboys.

It hit me like a branding iron. John Wayne, by then the symbol of rugged American masculinity, played the aging rancher who takes a group of boys on a cattle drive. Roscoe Lee Browne was amazing as the cook and brought dignity and quiet strength in a way rarely given to Black actors at the time.

Bruce Dern is the best bad guy ever. He was slimy and frightening as the villain, made the danger feel real, and the band of unknown boys made the story feel like it could have been any of us. If you’ve never seen The Cowboys, stop right here. I’m about to give something away.

The shock came when Wayne’s character was gunned down – by Bruce Dern. For kids in my generation, the Duke wasn’t supposed to die. Heroes always made it to the end of the movie. Suddenly the world seemed more fragile. And Bruce Dern was so real to me; I wanted to see him get his.

The Cowboys was a reminder that the right story, told boldly and with Wayne’s gravitas, could extend a studio’s fortunes while teaching kids like me that manhood carried a price.

Of all the films of that era, 1968’s Planet of the Apes and its sequels had the deepest philosophical bite for me. It is the story of American astronauts traveling to the future, where apes are in charge and humans are in captivity.

Charlton Heston played astronaut George Taylor, while Roddy McDowall and Kim Hunter, buried under groundbreaking makeup, gave the apes more humanity than many of the humans.

Written by Michael Wilson and, most importantly for me, Rod Serling (the same Serling who had already twisted my young mind with The Twilight Zone) the story was a treatise on race, war, science, and what it means to be human.

Planet of the Apes became not just a hit, but also a franchise: four sequels, a TV series, and eventually the kind of long-running property that studios dream about.

If you haven’t seen Planet of the Apes, stop right here. I’m about to give away the ending.

When Heston discovered the ruined Statue of Liberty buried in the sand, it was Serling’s voice whispering: “Civilization can destroy itself.”

My generation grew up suspicious of easy answers. We learned that authority could be flawed, that heroes could die, that humanity itself might be on trial, and that danger was never far away.

Those movies gave us both fear and hope. They didn’t just entertain us; they saved studios, defined an era, and reminded us that even in the South, far away from Hollywood, the world was bigger, scarier, and more thought provoking than we could imagine.

Hindsight, I realize those writers, actors, and studios succeeded at something rare: they gave kids like me both nightmares and wisdom. They told us that the world isn’t safe, and it isn’t simple.

Always, something to think about.

© 2025 John Moore

John’s, Puns for Groan People (a book of dad jokes); and two volumes about growing up in the South called, “Write of Passage,” are available at TheCountryWriter.com. John would like to hear from you at John@TheCountryWriter.com.

SEP

2025