My grandfather’s shop seemed cavernous. Every room was filled with tools that a man with a strong back could use to make a living and feed his family.

My grandfather was a blacksmith. His name was Parmer.

He was a product of the Great Depression. Born in 1918, he arrived at adulthood in the midst of the worst economic period in American history. But, like many men and women of that era, he was raised in a family that survived not on money (they had very little), but on knowledge and hard work.

No doubt, the Depression affected him, but families were more self-reliant then. What you ate, you raised or grew. Your land provided your sustenance, and your family and friends taught you a trade.

Parmer’s father was also a blacksmith. In his father’s shop, my grandfather learned blacksmithing. He apprenticed under his father until he was good enough to move away and start his own business.

For the next 40 years, the hammer and anvil were his living.

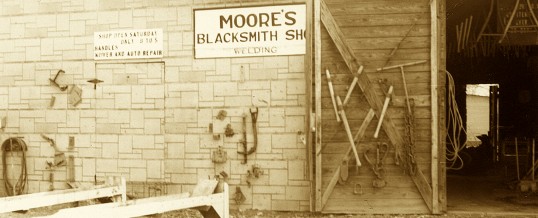

My earliest memories of his shop are of him holding a cup of percolator coffee; the 7 Up machine sitting near the big front doors, the Frostie Root Beer clock that hung above it, and the radio next to the clock. As I would follow him from room to room, Patsy Cline, Faron Young, Loretta Lynn, and other country music stars would sing to us.

I watched him work. It seemed there wasn’t anything he couldn’t do.

His customers would arrive with something broken, and they would leave with it fixed. It made me proud.

He could repair plows, replace hoe, axe or rake handles, and he could weld.

Before modern arc welders, which require electricity, there was the blacksmith. I was fortunate to witness a period where the old and the new converged. My grandfather did use an arc welder, but more often than not, he would fire up his coal forge and weld the old-fashioned way.

Heating up two pieces of metal and hammering them together on an anvil is the original way to weld.

He welcomed me to learn how he did it. I would watch as the fire in the forge turned the coal into glowing mounds. He would take a piece of stock metal, sometimes round, sometimes square, stick it in the forge and heat it until the coal was just the right color. He’d then move the metal he was working to the anvil, where he’d firmly hold it with his left hand and come down hard on it with the hammer in his right.

His left hand would turn the metal as he worked, allowing the hammer to shape it into what he wanted. When the metal would cool, he’d place it back in the forge and heat it up again, and then move back to the anvil. He continued until he had what he wanted.

Near the forge was a grinder. Under the grinder was a small washtub that he kept full of water. When he was done making what he wanted, he would dip the still-hot piece of metal in that tub. I can still hear the sound that it made.

My grandfather believed in self-reliance. Instead of buying a replacement part, he made his own. Never buy anything that you could make yourself.

Even the sign on his building, which read, “Moore’s Blacksmith Shop,” was made of a piece of recycled metal.

He built his own forge. The bottom was a repurposed porcelain oil company sign, and the outer trim was a metal wagon wheel ring.

From the time of my first memories of him until I was 15, my grandfather taught me how to be my own man. He left us suddenly, way too young, at age 60.

Unable to bear the sight of his shop, my grandmother sold off its contents and had the building torn down. After the shop was gone, the remaining concrete slab finally revealed to me how small his shop actually was. Staring at the slab when I was older, I realized that it wasn’t the physical footprint he had left that mattered. It was his God-given footprint that had made the difference in so many lives.

My father was given one of the anvils and the shop sign, which a few years ago, he gave to me. Receiving these treasured items, I set them up in my shop and signed up for a blacksmithing class. I began to wonder what had happened to the forge.

My mother remembered who had bought it. Ironically, it was the doctor who had delivered me. But the doctor had passed away not long after my grandfather. I began my search to reunite the anvil and the forge. Amazingly, I was able to track down the doctor’s grandson in Houston. I explained to him who I was and that I wanted to buy it back. He remembered where the forge was. It still sat in the same barn in Ashdown, Arkansas, where his grandfather had placed it the day he bought it. He agreed to sell it to me. I traveled to the barn and retrieved it.

It almost seemed as if the forge had been placed there to wait for me to one day find it and bring it home.

On weekends now, I like to head down to my shop early in the morning with a cup of percolator coffee. I open the big front doors and turn on the radio. Patsy Cline, Faron Young and Loretta Lynn sing to me. Thanks to what my grandfather taught me, some days I use his old anvil to make or repair a part I need instead of buying one.

The sign resting above the anvil and me is faded, but it still clearly reads, “Moore’s Blacksmith Shop.”

©2016 John Moore

For more of John’s musings, visit johnmoore.net/blog

JUL

2016