There’s a rhythm to the seasons that you can feel in your bones when you grow up in a place like southwest Arkansas.

Long before supermarkets swallowed up every bite of our food into cellophane and fluorescent lights, there was a time when what you ate came from the land, and you knew the taste of the seasons.

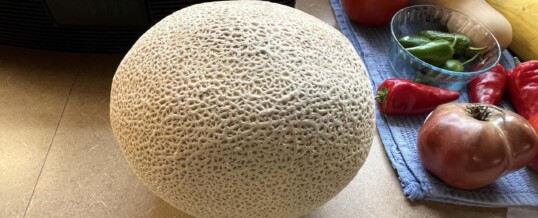

I grew up in the South in the 1960s and 70s, when a hot summer day might find us driving the winding roads around Ashdown, Nashville, Horatio, and DeQueen. We’d have windows down, engine humming, and my dad scanning for the telltale signs of a roadside stand. He could spot a stack of cantaloupes or a hand-lettered “Fresh Peaches” sign from a quarter mile away. And when he did, he’d ease the Buick onto the gravel shoulder and step out with the kind of reverence you might show when entering a country church.

Dad loved fruit—not just as a snack, but also as a meal. We all did. Cantaloupes so ripe they split with a spoon, and as sweet as sugar.

Peaches with juice that ran down your arms before you could get the first bite down. Crisp pears and tart apples from trees that had seen many changes.

Sometimes, if we were lucky, the old man selling them would toss in a few overripe ones for free, “for making preserves,” he’d say with a wink.

I didn’t realize it then, but those backroad stops were more than pit stops. They were lessons—quiet ones—about slowing down, about knowing where your food came from, and about honoring the work of the people who grew it. We’d sit at a roadside park, or sometimes just peel the paper sack open on the front seat, eating right there with sticky fingers and sun-warmed smiles.

And then there were the peanuts.

Every year, Dad would come home with a burlap sack slung over his shoulder—raw peanuts, freshly dug. It was as if he’d found treasure.

In our red brick house on Beech Street in Ashdown, the kitchen would take on a new scent: not sweet this time, but earthy and rich. He’d spread the peanuts on an old cookie sheet, slide them into the gas oven, and let the heat do its magic. “Parched peanuts,” he called them—roasted to a crunch, skins flaking, and warmth still in their cores. We’d eat them by the handful, shelling and talking, the crack of peanut hulls mixing with laughter and whatever country station was playing on the radio.

Mom had her own way of turning the seasons into magic. When snow fell—rare, but when it did, it came soft and quiet—she’d grab a big bowl and scoop up clean snow from the top of the car. Back inside, she’d stir in milk, sugar, and vanilla until we had a heaping bowl of snow ice cream.

It wasn’t fancy, but it was something special. Cold and sweet and fleeting—just like the snow itself. We’d huddle by the fireplace, spoons clinking, our faces pink from the cold, grateful for something so simple and good.

Looking back, I realize it wasn’t just about the food. It was about the way we shared it.

There was something sacred about those roadside cantaloupes and kitchen-roasted peanuts, about that bowl of snow ice cream. It wasn’t just about taste—it was about time.

Time spent together. Time taken to enjoy something fresh and real. My dad didn’t talk much about feelings or memories. But I can still see the way his eyes lit up when he found a perfect peach or cracked open a peanut just right. That was his way of saying, “This is good. Life is good. I want to share this with you.”

Today, I can still find fruit at the store, even “local” produce sometimes. But it’s not the same. I don’t stop on the side of the road nearly enough. I don’t roast enough peanuts in the oven. And it’s been years since I’ve had snow ice cream.

But every time I bite into a ripe peach or smell roasted peanuts, I’m back there—in that car with dad, or in that warm kitchen with mom—remembering a time when food was more than something to eat. It was something to savor, something that brought us together.

We didn’t have much money, but we had fruit in summer, peanuts in fall, and snow ice cream in winter. We had family. And that made all the difference.

So the next time you pass a roadside stand, pull over. Buy the cantaloupe. Taste the peach. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll feel what many Southerners felt all those years ago on the backroads —something sweet, something simple, something that tastes a lot like love.

©2025 John Moore

John’s books, Puns for Groan People and Write of Passage: A Southerner’s View of Then and Now Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, are available on his website TheCountryWriter.com, where you can also send him a message.

JUL

2025